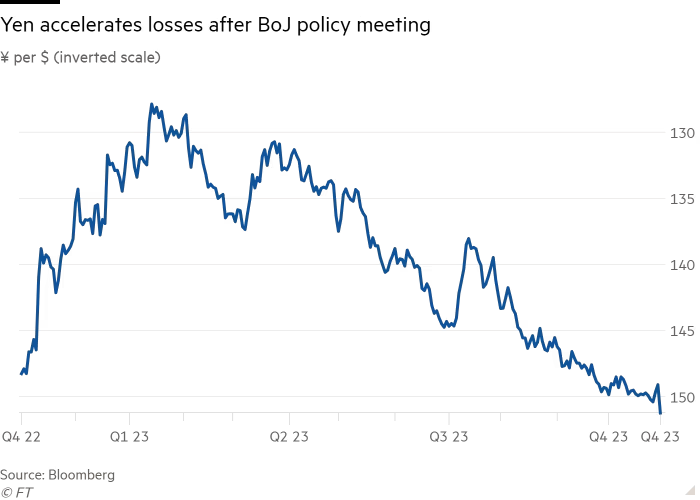

The yen suffered its biggest daily fall against the dollar since April on Tuesday after the Bank of Japan made only modest changes to its policy of holding down government bond yields.

The Japanese currency fell 1.7 per cent against the dollar to ¥151.60, its weakest level since October last year, and close to the point at which the central bank last intervened by spending a record ¥6.35tn ($43bn) to push the yen back up.

Some investors had suspected the BoJ would take a more definitive step towards closing the gap between borrowing costs in the US and Japan by abandoning its yield curve control altogether, as the yen tests multi-decade lows and inflation has persisted above the central bank’s target for the past 18 months.

Instead, officials changed the 1 per cent limit on 10-year Japanese bond yields from a hard cap to a “reference point”. “The fact that the yen weakened by more than a percentage point is the market telling you that they still think the Bank of Japan is behind the curve,” said Ella Hoxha, head of fixed income at Newton Investment Management. “That’s fair because inflation is much higher than their 2 per cent target and they are the last central bank standing in terms of very loose policy.”

Analysts predict Japanese officials are poised to intervene and support the currency again if the currency continues to weaken to a 32-year low, estimating it might step in at levels between ¥152 and ¥155. “They are probably quite comfortable with where Japanese government bond yields are and relying on intervention to prevent the yen getting out of control,” said Chris Turner, head of global markets at ING.

The central bank maintained its policy rate at minus 0.1 per cent, the world’s only negative interest rate. But it significantly increased its inflation forecast, saying it expected 2.8 per cent core inflation in the 2024 fiscal year, instead of its previous forecast of 1.9 per cent.

Analysts say the fall in the currency puts the BoJ in a bind, as it pushes up the cost of imported goods, when officials are focused on achieving domestically driven inflation for maintaining a 2 per cent target rate.

The yen has been the worst performing major currency this year, falling by over 13 per cent against the dollar, fuelled by the yawning gap between US and Japanese borrowing costs. Intervention on its own would be unlikely durably to support the sliding yen — that would depend more on a switch in US monetary policy that pulls down the dollar or on a push higher in Japanese interest rates.

But that too brings potential risks. “They are trying to support the currency while not being seen as tightening,” said Eva Sun-Wai, fund manager at M&G Investments. “If they let yields run much higher when they have so much debt they run the risk of not being able to refinance at higher levels of interest.” However, investors think it is inevitable that the BoJ will normalise policy as the economy remains buoyant and inflation remains persistently above target. Sun-Wai said that her worry is that the longer policymakers leave it to tighten, the tougher they will have to be.

The normalisation of policy in Japan could have major ramifications for international bond markets, as Japanese investors own trillions of dollars of overseas debt following years of hunting for higher yields elsewhere.

“Under Governor [Kazuo] Ueda’s leadership, the BoJ is moving to a more pragmatic approach,” said Iain Stealey, international CIO for fixed income at J.P. Morgan Asset Management. “We expect the BoJ to take a more active approach from here, potentially ending negative interest rates . . . as early as spring next year.”

Source : Financial Times